Glory Road: the movie’s good, but the truth’s better

February 28, 2020

In the middle of the film Glory Road, the Texas Western Miners were traveling to a game, but on their way, they stopped at a Southern restaurant that had a “whites only” sign on it. When one of the players needed to use the restroom, four of the white customers beat him up and shoved his head into a toilet, some of them urinating on him while others held the player down. This revolting scene spotlights the many examples of atrocity, bigotry, and prejudice that many people faced throughout the last century in our country. The purpose of the film is to help the audience see how and why our society moved away from that kind of behavior and thinking.

It is true that Glory Road was inspired by facts; the novel became a national bestseller in 2005, released by Hyperion Books. The plot focuses on the 1966 Texas Western men’s basketball team’s struggle to reach the national championship and to deal with the reactions society had regarding their accomplishment (Arnold).

After being appointed head coach in 1966, Don Haskins, who is played by Josh Lucas, decides to develop a great team based on talent instead of race; the majority of other coaches were focused on maintaining an all-white team. The film and novel emphasize that a new, diverse lineup has the world and the townsfolk talking, even though racial tension builds, but the team becomes so dominant on the court with their flashy playing style that they win almost all their games, and it begins to win people over to the idea that acceptance is the key to success.

However, it is not an easy road to success and acceptance. The team’s only loss comes in a game that involves a racial issue; some of the black people on the team like Bobby Joe Hill, played by Derek Luke, and team captain Harry Flournoy, played by Mehcad Brooks, think that they are not being supported, that others don’t know how it feels to deal with racism. As the team learns to overcome challenges on and off the court, they finally become the first team in history to field an all-black starting line-up in the NCAA title game. The players face an all-white team from the University of Kentucky (Arnold).

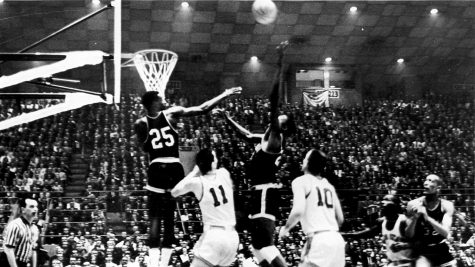

Although the plot of Glory Road is exciting; the truth behind black athletes’ influence on basketball is even more inspirational and much more far-reaching than a single season in the NCAA. Also the Texas Western Miners were not the first team with black players to win the NCAA championships. In 1962, the University of Cincinnati won it all with four black starters. Many sportswriters and opponents stated that the Bearcats were a remarkable group and terrifying to play against. Bonham, Hogue, Thacker, Wilson and Yates were named All-American at different points in their college careers; Wilson later won a gold medal for the United States in the Olympic Games (DeCourcy). So, without a doubt, truth is better than fiction, since the 1962 Cincinnati Bearcats really changed the pace of the game and also the whole manner in which basketball is played.

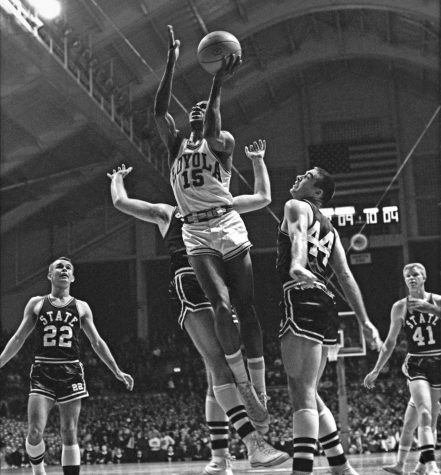

There was clearly a progression that moved the country closer toward racial equality, but a year later in 1963, “Loyola-Chicago broke racial barriers” (Mather). This team also featured a predominantly black line up. In the National Championship, Loyola faced an all-white team from Mississippi State, as civil rights battles raged across the country, but the South in particular had several events going on during this time that heightened tensions at the game: the date marking the first black student to enroll at the University of Mississippi was that same year, setting off deadly riots by angry whites. However, after Loyola-Chicago’s success in this big game, colleges across the south started accepting black students (Mather).

Clemson, Tulane and Southwest Texas State each earned national championships with desegregated line ups. Additionally, in the NBA, hall of famers like Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, Oscar Robertson, and Elgin Baylor were already developing new strategies, skills, and shooting forms before the middle of the 1960s. In the movie, Glory Road, people couldn’t conceive of the idea that there would be black NBA hall famers or that black athletes might change the landscape of the game, but as we see, in real life they had already begun to do just that (DeCourcy). These talented men were so big, clever, and athletic that they changed the way that everyone in the entire world plays the sport.

Works Cited

“’Glory Road’ Plays Fast and Loose with Facts.” NPR, NPR, 21 Jan. 2006, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5166582.

DeCourcy, Mike. “1962 Cincinnati’s Barrier-Breaking Title against Ohio State Echoes in 2018-19 Opener.” Sporting News Canada, (Courtesy of University of Cincinnati), 8 Nov. 2018, www.sportingnews.com/ca/ncaa-basketball/news/1962-cincinnati-barrier-breaking-title-against-ohio-state-echoes-in-2018-19-opener/bbpg4vu6ksdn1tfjvxjoj1302.

Mather, Victor. “When Loyola-Chicago Broke a Racial Barrier 55 Years Ago.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 Mar. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/03/29/sports/loyola-chicago-1963-ncaa-tournament.html.

William Arnold, P-I Movie Critic. “Hollywood Takes Liberties with True Stories but ‘Glory Road’ Is a Flagrant Foul.” Seattlepi.com, Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 18 Mar. 2011, www.seattlepi.com/ae/movies/article/Hollywood-takes-liberties-with-true-stories-but-1195421.php.

Pictures